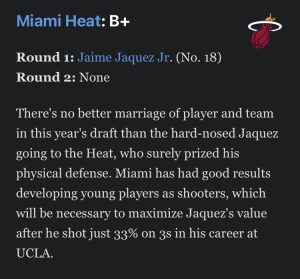

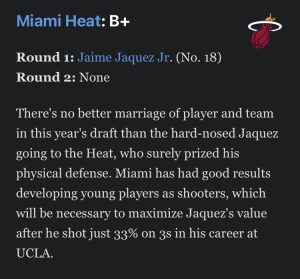

Kevin Pelton is one of the best writers on ESPN and included this review of the Miami Heat’s pick in his overall review of the 2023 NBA Draft. This is a familiar refrain within the NBA and NBA media: Miami Heat develop players, and especially shooters. I am a Miami Heat fan and believe Eric Spoelstra is the best coach in the NBA, but, to me, this demonstrates the idea that once repeated enough, an idea becomes a fact.

People oftentimes confuse scouting and development, or at least the line between scouting and development is blurred and difficult to separate. The Heat play an unusually high number of undrafted players, which we equate with great player development. Why not scouting? Why not coaching?

We assume players must have improved greatly to go from undrafted to rotation players or G-League to NBA starters because we largely ignore the effect of environment on player performance. The Heat likely are the best organization at identifying the players who fit their style, their system, and their organization. They know who they are, and what they want, largely because of consistency and alignment in management and coaching with Pat Riley and Spoelstra. These players may excel in Miami simply because the organization identifies players who fit, and Spoelstra and staff give them opportunities and the confidence to play to their strengths and play through mistakes.

This is not to discount the coaching or the player development. Clearly, something happens to certain players in Miami, whether scouting, playing time, coaching, system, player development, or a combination. Miami is the NBA’s model franchise (along with San Antonio). However, even with the models and the best organizations and coaches, some comments can be exaggerated, especially in an era that demands near constant content, lists, rankings, and more.

The Heat is known for its culture, and especially the emphasis on toughness and fitness. Many players avoid the Heat; its culture helps to self-select only players with a certain profile, and one that tends toward hard workers and coachability. Player development and role acceptance is easier when players choose to play for you with this understanding.

The current players who have been used to demonstrate the Heat’s player development are Duncan Robinson, Max Strus, Gabe Vincent, and Caleb Martin. Each is a tremendous story in his own right, examples of perseverance, work ethic, and overcoming obstacles that typically exclude players from the NBA. Again, each is an example of scouting, the Heat identifying specific players to fit specific roles, and players working hard and accepting their roles. Miami is selective in its talent identification, willing to take less heralded players who fit their model rather than sign more heralded or higher ranked players who may not fit. Miami knows who it is and who it wants, and these four appear to share those qualities.

However, as examples of the Heat developing shooters, the evidence is less convincing.

Duncan Robinson is the true home-grown talent, an undrafted player who started his college career at an NCAA D3 program and spent a year primarily in the G-League before ascending to near superstardom in the Bubble. Robinson’s three-point shooting statistics are hard to believe.

His percentages decreased year by year through all three seasons at the University of Michigan, shooting 45%, 42.4%, and 38.4% from the three-point line. Somehow, after ignoring his rookie season in which he played sparsely, primarily in the NBA G-League, his three-point field goal percentages have declined year by year with the Heat: 44.6%, 40.8%, 37.2%, and 32.8%.

I have never seen such consistent regression in different settings. Robinson truly is an anomaly, and not just as an NCAA D3 player in the NBA. However, he provides no evidence of the Heat’s effectiveness in developing shooters, and potentially demonstrates the opposite, although his overall games has improved, as evidenced by his cutting and finishing late in the playoffs and the NBA Finals.

Max Strus is an almost true home-grown talent as another undrafted player. Strus started his college career at an NCAA D2 program prior to transferring to DePaul for his final two seasons. He spent his rookie season with the Chicago Bulls’ G-League team, but tore his ACL early in the season, meaning his rookie NBA season was spent primarily in rehab.

He has improved in his second season everywhere he has played. At Lewis, he shot 35.2% and 36.0% in his two seasons. At DePaul, he shot 33.3% and 36.3%. In the NBA, discounting the few months in the G-League as a rookie, he shot 33.8% in his first season in Miami, followed by 41%; his shooting dipped to 35% on three-pointers in his third season.

Many of my junior-college players had similar ups and downs. They improved in their second season playing for me, then their percentages decreased in their first seasons after transferring before rebounding in their fourth seasons as they adapted to the new coach and new level. We should expect players to improve between their first and second seasons at almost any level due to adapting to the new demands, coach, teammates, system, and more.

Strus’ fourth NBA season will be interesting; does his three-point shooting percentage rebound back to 41% or higher or was that season an anomaly, and he is closer to a 35-36% as his total career averages suggest?

Gabe Vincent is another player used as an example of Miami’s player development as an undrafted player from the Big West Conference (UCSB) who spent time in the NBA G-League before breaking through. However, he started his NBA G-League career with Sacramento’s G-League franchise, not in the Heat organization.

Vincent’s three-point shooting percentages in his four years of college declined until his senior season: 41.6%, 38.5%, 32.9%, and 37.7%, for a total of 37.6%. Next, he played most of two seasons for the Stockton Kings before moving to Sioux Falls, the Heat’s G-League franchise, for the final 11 games of his second professional season in 2019-20. He improved from 29.1% as a rookie to 42.1% through 24 games in his second season with Stockton, and 36.9% in the final 11 games with Sioux Falls, for a total of 40.3% in his second G-League season. He was named NBA G-League’s Most Improved Player for the 2019-20 season.

He played limited minutes with Miami in 2019-20, shooting 22.2% on 27 3FGA. In his three full seasons with the Heat, he improved from 30.9% to 36.8% and then back to 33.4%.

His three-point shooting percentages are all over the place, but history suggests he likely is better than his 2022-23 percentages. However, his shooting percentages in Miami do not demonstrate shooting development, as he has shot worse than his percentages in college and the G-League (although obviously against better talent/defense). I imagine his shooting stabilizes around 36%, like his second season and similar to his college percentages.

Caleb Martin certainly turned heads while playing for the Heat, but the Heat was not his first NBA team. Martin also played four years of college basketball, starting at NC State and finishing at Nevada. He shot 30.5% and 36.1% at NC State before sitting out for one season as a transfer. In his first season at Nevada, he shot 40.3%, before dropping to 33.8%.

In limited appearances as a rookie for Charlotte, he shot 54.1% (20/37), but dropped to 24.8% in his second season. In his first season in Miami, he bounced back to 41.3%, and then fall to 35.6%.

His shooting has yet to show consistency from year to year, although this may be the first time he has settled into a consistent role and playing time. I would expect him to stabilize as a roughly league-average three-point shooter in the 36% region.

These four certainly performed better in Miami and became legitimate NBA contributors and starters, which few would have predicted during their NCAA careers. Something positive happens in South Beach, and Jaime Jacquez fits a similar profile as a four-year, experienced player, despite being a 1st Round pick with greater notoriety and expectations due to his UCLA career. Jacquez saw a big jump in his sophomore season in three-point field goal percentage, then regression for his final two seasons: 31.3% to 39.4%, then 27.6% and 31.7%.

In each instance, Miami identified players who had had shooting success previously, although their percentages had dropped, likely contributing to their availability. They were older for the potential curve, closer to their peak than drafting and developing an 18 or 19-year old, but this also provided more film, and a more knowledgeable evaluation.

Miami is known as a franchise that does things its own way. Their foundation — from ownership to Riley to Spoelstra — and their culture self-selects players who are more mature and maybe who have something to prove. Their culture, environment, and talent identification seem to be second to none, but their shooting development appears overstated based on the statistics. In several cases, it seems whatever transitions or changes occurred between year 1 and year 2 in the Heat organization need to be continued to maintain consistency for subsequent seasons.

All stats from Basketball Reference.

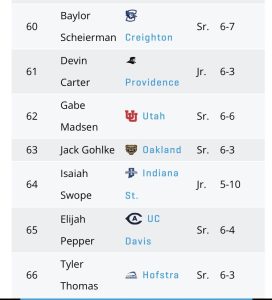

He shot 37.6% from behind the three-point line this season, which ranked 63rd in NCAA Division 1 men’s basketball, roughly the same as our team’s shooting percentage.

He shot 37.6% from behind the three-point line this season, which ranked 63rd in NCAA Division 1 men’s basketball, roughly the same as our team’s shooting percentage.