Prior to Evolution of 180 Shooter: A 21st Century Guide, I remarked that my team did not do any form shooting during our practices, while shooting 37.4% from the three-point line and 72.6% from the free-throw line, both of which ranked in the NJCAA top 10. Naturally, someone replied, “Maybe you would have shot better if you did form shooting.”

Most coaches believe form shooting (Fake Fundamentals, Vol. 3) is the first step to great shooting performance.

If your shooting workouts don’t incorporate form shooting close to the basket, you won’t reach your potential as a shooter.

— Coach Mac 🏀 (@BballCoachMac) March 30, 2024

Therefore, incorporating form shooting should improve anyone’s shooting percentages regardless of current success. Nobody questions form shooting’s effectiveness despite the differences between most form shooting and game shots. Most great shooters start with form shooting, which confirms our beliefs. Form shooting is important, and it works, and therefore it is logical to suggest we would have improved by incorporating form shooting despite ranking in the top 10 in three-point and free-throw shooting. Few disagree.

We do not live in the multiverse, or at least we currently cannot access it, so we cannot test this hypothetical. We cannot re-play the season with the same players attempting the same shots against the same opponents, but with different practice drills. The statement is unfalsifiable.

People hold onto their beliefs, rather than accept evidence to the contrary, because we have confirmation bias, which is the tendency to favor information confirming or strengthening one’s beliefs or values, while disregarding contradictory information. My example of elite shooting without form shooting is dismissed and does not affect entrenched beliefs.

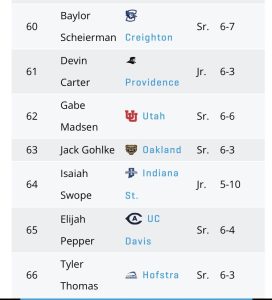

I thought of this as people posted about Oakland University’s Jack Gohlke’s workouts after his monumental NCAA Tournament performance. Gohlke made 10 three-pointers against Kentucky, one short of the NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament record, and another six in Oakland’s second-round loss.

He shot 37.6% from behind the three-point line this season, which ranked 63rd in NCAA Division 1 men’s basketball, roughly the same as our team’s shooting percentage.

He shot 37.6% from behind the three-point line this season, which ranked 63rd in NCAA Division 1 men’s basketball, roughly the same as our team’s shooting percentage.

Nobody questioned Gohlke’s shooting routine. Nobody suggested a different approach would have led to more success or better shooting percentages. Instead, coaches created posters to hang in their locker rooms to demonstrate to their players the work required to succeed at the NCAA Division 1 level.

The message is important; success requires effort and dedication. However, coaches latched onto this message, as opposed to my message about the lack of form shooting, because it fits their current beliefs. Gohlke’s extensive shooting routine confirmed their bias toward repetitions, practice hours, and grinding.

Nobody cared that while he is a great shooter, he was far from the best shooter this season. We played at a different competitive level, and obviously different genders, but our team had five shooters shoot better than 37.6% from the three-point line, and four on reasonably high volume (To preempt criticism, the best men’s shooter I trained as a shooting coach shot 42% from three-point line for his NCAA D1 career with a season-high of 46.1% and broke conference three-point shooting records).

One may argue shooting is more difficult in NCAA men’s basketball than women’s basketball, but statistics argue differently. NCAA D1 men’s basketball averaged 33-34% from the three-point line in the regular season this year, compared to 31-32% for NCAA D1 women’s basketball. From that perspective, our percentage was further from average than was Gohlke’s. Here are the shots from our 5th best shooter (by percentage) who was near his season percentage:

This is not to take away anything from Gohlke, as he is a great shooter who had a great season and provided the biggest highlight of the first weekend of the Men’s NCAA Tournament. Instead, this simply is to demonstrate our confirmation bias when it comes to skill development, shooting, practice design, and coaching. Coaches hold onto their beliefs, and find examples to confirm their biases, rather than search out new information or try new things that may help their players improve more or perform better during games. They rely on repetitions as the magic cure; but how many repetitions? Nobody can say.

Nobody will suggest, “Maybe if he practiced less or practiced differently he would have shot even better” because people believe in repetitions, block practice, and spot shooting. Coaches want their players to invest in this practice, even when other practice led to better results.

In all likelihood, any player investing this much time in shooting will improve. 750 shots in a day is a lot of shots. At the end of the day, that is the ultimate goal, regardless of the practice design.

What if the time spent accumulating these repetitions to demonstrate slight shooting improvements meant less time to improve weaknesses, such as speed, defense, dribbling, and more? He shot 38.2% for his NCAA D2 career, and 40.0% in his final NCAA D2 season. There are different ways to demonstrate shooting improvements, but his shooting percentages have been consistent since he began to receive consistent playing time. Maintaining those percentages at an NCAA D1 level against theoretically better, bigger, faster defenses is one way to demonstrate improvement. However, he also took eight shots inside the three-point line all season; maybe the volume of shooting practice prevented other improvements.

Coaches resists change because of confirmation bias due to examples such as Gohlke. A huge volume of practice led to a great shooting performance. See, practice more. Get your butt in the gym.

Just as I cannot prove form shooting would not have led to better shooting with my team, I cannot prove Gohlke would have shot the same or better percentage with less or different practice. It is unfalsifiable.

My evidence for our practice, however, is our players. Almost without exception, they shot lower percentages before and after their two junior-college seasons. This is a within-subjects design: We can compare the results from the same players who encountered two or more different training environments. Of course, it is far from objective, as too many variables affect shooting performance: Most prominently, different competitive levels, but also shot selection, system of play, coach, teammates, defense, and more. For all I know, our shooting success was largely due to the players liking each other or playing together in a positive emotional state as opposed to the other environments in which they played before and after transferring. Practice design may not have had any effect.

However, for the most part, players changed their practice during their two years at junior college, engaging in more contested shooting and decision-making shooting practice through small-sided games and modified shooting drills than before or after. Many, once transferring to NCAA D1 programs, never practiced these shots again. Some teams used only isolated, block shooting drills during practice; others did not even practice shooting, relying instead on players to shoot on a shooting machine on their own time. Many coaches view our shooting drills as scrimmaging or playing and not true skill development, and do not incorporate them.

The players went through many changes when they transferred. It is difficult to compare situations, systems, styles of play, shot selection, playing time, opponents, and more. However, every single player shot better when practicing with more variable, defended, and decision-making shooting drills than when they no longer engaged in this practice.

Of course, this does not confirm the typical coaching bias, so coaches ignore these results, and attribute the differences to playing at a higher level (which is debatable, as we played opponents with multiple high-major players, whereas most of our players transferred to low-major programs) or the players not practicing hard enough.

This is not to suggest repetitions play no role in shooting development, nor is this in any way a criticism of Gohlke. Instead, this simply demonstrates the power of confirmation bias and seeking information to affirm our beliefs rather than questioning our current processes. How can we develop better players, or develop into better coaches, if we only trust the information confirming our current beliefs?