The answer for improvement or skill development is more: More time, more reps, more practice. How many more? How much time or practice is required? Many coaches cite the 10,000-hour rule, but none exists (see Fake Fundamentals, Vol. 3 for more information).

When more is emphasized, the how is de-emphasized. Instead, anything that looks good or looks like it practices something important is called skill development.

I posted this drill last week; this is from the morning shooting workout for a professional team. Many would suggest this is skill development. The shots are directly from our sets and, for many, are “game shots from game spots at game speeds” (see Fake Fundamentals, Vol. 2 for why I would not). People liked the drill and commented on its use of different skills. This is just a drill to me; it is not skill development.

We used this drill at the morning practice, which was followed by an evening team practice, on the day before a game. I took over the team midseason with the schedule and expectations set. I would change things if I was in complete control. The purpose of this workout, especially the day before a game, was to “get up shots”: Increase confidence by seeing the ball go through the hoop. This is focused on performance (game the next day), and not learning (long term). It worked, I suppose, as the players pictured combined to go 10/19 from the 3-point line the next day. This, of course, is performance; one game does not mean we shoot 53% from behind the 3-point arc.

I like the drill, as drills go, because it combines multiple skills; it’s variable, random practice: The drill incorporates different versions of different skills in each repetition. The two-ball dribbling forces different passes; players employ different finishes; and the shots, while similar, vary slightly from rep to rep because of the movement. The timing, the catch, the footwork, the location, and more vary. From this standpoint, the drill is better than a spot shooting drill with one player attempting X shots in a row. Despite its apparent success, and the positives, I still consider this a drill, and not skill development. How do we differentiate “skill development” from “drills”?

What is skill development? Skill is “is the learned ability to bring out the pre-determined results with maximum certainty, often with the minimum outlay of time, energy or both” (Knapp, 1963). Development is “the process of developing or being developed”, which is “to grow or cause to grow and become more mature, advanced, or elaborate.” Therefore, we might say skill development is the process of growing, advancing or making more elaborate the learned ability to bring out the pre-determined results with maximum certainty, often with the minimum outlay of time, energy or both.” In terms of shooting, skill development improves accuracy (increased shooting percentages), but also builds more advanced or elaborate skills: Increased range, quicker release, harder shots (step-backs), and more.

In context, skill development is the process by which one improves skill. Ultimately, these improvements are measured through game performance. Therefore, when discussing drills in the context of skill development, we should understand how the activity impacts one or more aspects of the skill (accuracy, distance, quickness) and transfers to the game.

This drill is not “game shooting” because there was no defense or decisions. Deciding to shoot is a part of game shooting (see Evolution of 180 Shooter: A 21st Century Guide for more), but the drill determined the specific shooter on each repetition. The drill does not practice or improve “game shooting” directly because shooters do not improve their reading of the defense, feel for openness, perception of a defender’s proximity, and more. Any improvements must be more indirect, as the shooting is removed from the game context, despite it appearing similar to the shots from one of our sets.

This is where the drill, and more drills, fall short. This is a group activity, a team drill. Each player performs the same skills. From a general standpoint, this is good: You can see our starting center practicing 2-ball dribbling drills and making one-hand passes off the dribble. For some, these skills improve slightly because of lack of previous exposure: A player who has never dribbled 2 balls will improve her ability to dribble 2 balls through this drill, just as someone who rarely has practiced one-hand passes will improve this ability through increased exposure/repetitions. However, this was primarily a shooting drill (“get up shots”), and none of the players lacks previous exposure to shooting jump shots.

How does a player improve individually through a team drill? Does this drill meet the specific needs of each player? Does it improve shooting accuracy? Speed? Range? Footwork?

It is possible. I instructed players to pick one thing to improve in drills rather than expecting magical improvements from doing drills. My guess is, at most, 2 players in this group listened and changed their behaviors (concentration, focus, emphasis). There may be something specific they are practicing; one player is trying to quicken her release by limiting the dip on her shot. It is possible, if she concentrates, this drill (and others) can improve her shooting through this mechanism. However, this is not the specific drill I would choose to focus on that specific change; there are better, more specific drills.

Drills are a tool; they are not skill development. They may assist with skill development when used correctly by players and coaches, but performing a drill is not skill development. Too often, we rely on doing more to improve players, and every year, this approach fails players. There are different ways to improve a skill such as shooting, and when designing drills, whether for an individual or a group, we should understand the processes by which we expect the drill to improve accuracy, speed, or skill elaboration and transfer to the game. Without that understanding, and without the proper feedback from the coach and concentration from the player, drills are just work; exercise and activity one hopes may impact future performance positively.

FAQs

What are some specific examples of “game-like” shooting drills that can bridge the gap between drills and in-game performance? “Game-like” shooting drills require defenders, decision-making, and at least one passing option. For example:

Coaches should customize drills to mimic the pace, intensity, and decision-making aspects of real games.

How can a coach or player assess whether their shooting drills are effectively translating into improved game performance? Assessing the effectiveness of shooting drills involves tracking performance metrics over time. This could include shooting percentages from different spots on the court, shot selection during games, and overall shooting accuracy in game situations. Video analysis can also be helpful, allowing players and coaches to review how well the skills practiced in drills translate to actual game footage. Additionally, feedback from coaches, teammates, and self-reflection can provide valuable insights into whether the training is making a difference in game performance.

Are there any potential drawbacks or pitfalls to avoid when designing or implementing shooting drills for skill development? When designing shooting drills, avoid drills that don’t translate well to actual game situations. For example, overly repetitive drills that don’t challenge decision-making or shot selection may not improve game performance. Additionally, drills that focus solely on shooting without incorporating other skills like footwork, ball-handling, and court awareness might not be comprehensive enough. Another pitfall is neglecting to adjust drills based on individual player needs; what works for one player may not work for another. Coaches should be mindful of overloading players with too many drills, which could lead to burnout or diminished focus.

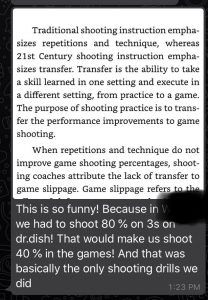

She never practiced shooting against defenders during the outlier season. Most of their shooting practice was on the Dr. Dish. Without the consistent game-like practice, she lost a sense of timing and rhythm and anticipating the speed of defenders, especially playing in a different conference against different opponents, then playing fewer minutes and shooting less. She no longer engaged in the same practice that helped her improve from 35% to 40%. The lack of game-like practice likely affected her confidence, compounding the problem.

She never practiced shooting against defenders during the outlier season. Most of their shooting practice was on the Dr. Dish. Without the consistent game-like practice, she lost a sense of timing and rhythm and anticipating the speed of defenders, especially playing in a different conference against different opponents, then playing fewer minutes and shooting less. She no longer engaged in the same practice that helped her improve from 35% to 40%. The lack of game-like practice likely affected her confidence, compounding the problem.