In an empty gym with no defenders, can you make that shot 7 out of 10 times CONSISTENTLY?

If yes, shoot that shot in games

If no, and you shoot that in games, your team probably won’t win much#ShotSelection

Room, rhythm, range

Winning shots > Instagram shots

— Sam Allen (@CoachSamAllen) July 18, 2022

There are dozens of tweets like this one, and nearly everyone agrees with the sentiment. Game slippage is real because everyone believes in game slippage. Players must shoot 70% in practice to shoot 35% in games.

The purpose of practice is transfer: We practice to improve, and we measure those improvements in games. We do not practice to become better shooters in a gym by ourselves; we practice to perform better in games. The discrepancy between 70% practice performance and 35% game performance demonstrates low transfer or a lack of transfer. As I wrote in Evolution of 180 Shooter: A 21st Century Guide, when game performance is halved from practice performance, not only is the transfer minimal, but we might suggest players are practicing a completely different skill.

The common coaching cliches all surround making practices harder than games. How do we suggest practice is harder than a game, while expecting players to shoot twice as well during practice?

Isn’t that kind of the point of this rule of thumb (which is obviously subjective)? Making 70% unguarded (no decision or other factors) means you probably make half of those shots in a game.

Small sample size but this rule of thumb tends to work on a % basis in my experience

— Mike Kenny (@mike_kenny3) July 18, 2022

We accept game slippage because we watch players like Curry make 105 three-pointers in a row in practice, and shoot 40% during games, and believe one caused the other.

Throwback to Steph Curry making 105 Threes in a ROW!! 🔥pic.twitter.com/xOJUuOFI0y

— NBA World (@NBAW0RLD24) July 19, 2022

“Complexity transfers to simplicity, but not vice versa.” – Rafe Kelley

All players who shoot 35% during games can shoot 70% by themselves in a gym, but not all players who shoot 70% by themselves shoot 35% during games. The 70% practice shooting does not cause 35% game shooting, but they are correlated because a great game shooter will be a great practice shooter as well. When we only look at the best, we trick ourselves into believing that correlation is causation. There are many great practice shooters who are not great game shooters.

During my first year as a college assistant, we had a backup point guard we nicknamed Hollywood. He was a practice hero. In practice scrimmages, he was often our best player. He spent the middle half of the season mocking a freshman who was re-learning his shooting technique because the freshman would not shoot 3s. Meanwhile, Hollywood would make three after three after three. This was a long time ago, so I do not remember exact percentages, but I’m pretty confident in saying that he shot in the 20s (teens?) from the three-point line during games. Meanwhile, the freshman eventually developed into a 180 Shooter later in his career. Hollywood’s practice performance did not transfer to game performance; he shot much worse than game slippage believers would estimate.

Here, however, is a more recent real life example of the effects of the game slippage philosophy. I recruited a player who shot 35% from the three-point line during her last season in high school. In her two seasons playing for me, she shot 34% and 40% and set the school record for three-point field goals made. A long-time NCAA Division 1 assistant coach called her the best shooter in the country during her second season (although she did not lead the team in 3FG%).

She transferred and shot 21% in her next season.

She transferred for her final season, which became two seasons because of the pandemic, and shot 35% and 37%.

Across those 6 seasons, she averaged roughly 37% from the three-point line (she had most 3FGA in the 40% season, and the fewest 3FGA in the 21% season). The outlier was the 21%. What happened? There are various factors involved: New coach, new teammates, new environment, new league, new offensive sets, new role, injuries, etc.

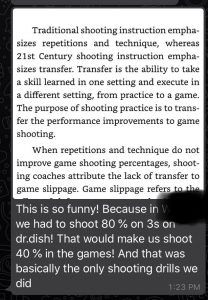

However this is a text she sent after she read Evolution of 180 Shooter:

In 6 seasons, one coach demanded 80% shooting in practice to shoot 3s in the games. She led the team or was near the lead during those Dr. Dish workouts, shooting around 80%, but she shot only 21% during games.

The issue was not her. This team did not shoot over 30% from 3-point line as a team for the season, whereas her previous team shot 37% and was top 5 nationally in 3FGM and 3FG%; her final team led the country in 3FGM, I believe.

She played for 3 coaches and 3 programs. Two programs were among the nation’s leaders in three-point field goals and three-point percentage. The other program believed in game slippage and Dr. Dish workouts to decide which shots players should take during games. Except the game slippage theory did not work, at least in her case (I don’t know other players’ practice percentages), as she was far off from her practice percentages during games.

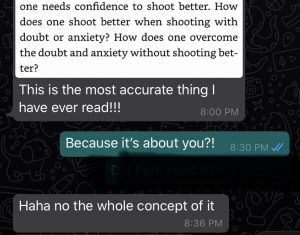

Why? Again, skill development and performance is multifactorial; I would not attribute success or failure to a single factor. However, in discussing her experience with her, two of the biggest factors were confidence and practice design.

She went from a team that encouraged her to shoot to one where she questioned her shots. Consequently her playing time went down, reducing her shot attempts, creating a negative reinforcement loop: Less confidence = worse shooting = less playing time = fewer shots = less confidence… This started with the coach (whose assistant had called her the best shooter in the country) creating arbitrary rules about who can shoot what shot based on practice percentages on a shooting machine. They also ran on treadmills next to the court for mistakes.

The second change was practice design. As she texted:

She never practiced shooting against defenders during the outlier season. Most of their shooting practice was on the Dr. Dish. Without the consistent game-like practice, she lost a sense of timing and rhythm and anticipating the speed of defenders, especially playing in a different conference against different opponents, then playing fewer minutes and shooting less. She no longer engaged in the same practice that helped her improve from 35% to 40%. The lack of game-like practice likely affected her confidence, compounding the problem.

She never practiced shooting against defenders during the outlier season. Most of their shooting practice was on the Dr. Dish. Without the consistent game-like practice, she lost a sense of timing and rhythm and anticipating the speed of defenders, especially playing in a different conference against different opponents, then playing fewer minutes and shooting less. She no longer engaged in the same practice that helped her improve from 35% to 40%. The lack of game-like practice likely affected her confidence, compounding the problem.

Is game slippage real? Sure, it’s called lack of transfer. It means players practice skills that are unlike the ones performed during games. Rather than buy into game slippage, we should create better practices, including as many game constraints as possible during drills and shooting practices. There are reasons not to use game-like or competitive shooting practice, such as the freshman who was re-learning his shooting technique through specific shooting practice, but most drills are general shooting practice, which has the lowest transfer to improvement and game performance. The purpose of practice is to improve game performance; when game performance is so far removed from practice performance, what are we really practicing?