The angst around the reduction of midrange jump shots confuses me, but Ben Taylor of Thinking Basketball provided an interesting look at the value of the midrange shot in the NBA, and specifically with the San Antonio Spurs.

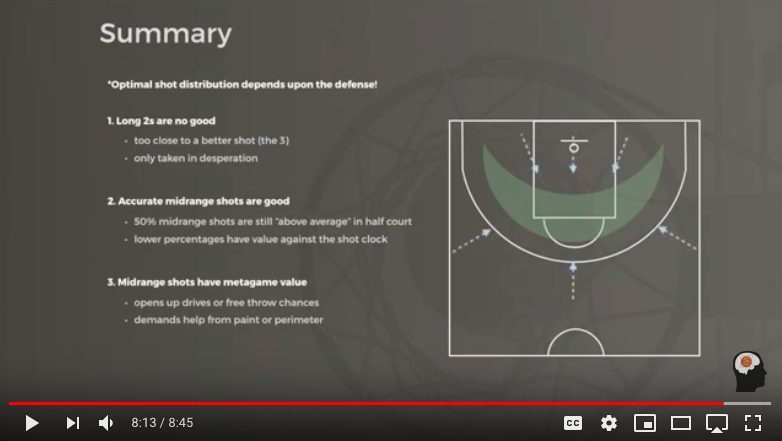

Here is a summary:

Taylor is accurate in that shots are not attempted in a vacuum, and one must account for specific variables to evaluate a specific shot. Of course, ESPN’s Kirk Goldsberry argued differently when Dame Lillard hit the three to end OKC’s season:

Dame's game-winner wasn't a "good shot" – it was a great shot. https://t.co/QtKpIQurzC pic.twitter.com/E7GduZ2qXt

— Kirk Goldsberry (@kirkgoldsberry) April 24, 2019

In a vacuum, a 40% shot is great offense in the half court, as Taylor’s video explained. However, on a game-winning shot with the game tied, is a 40% shot a good shot? If Lillard shoots 50% from midrange, isn’t that a better shot in that exact situation?

This is the difference between arguing about numbers (general, in a vacuum) and specifics. I lean toward 3>2, but there are times when any shot works or the highest percentage shot beats the highest efficiency shot.

Taylor’s argument about the midrange highlights good to great midrange shooters. This always had been my argument against long-range two-point jump shots.

A midrange jump shot is a more difficult, more complex shot than a catch-and-shoot three-pointer. Honestly, age and skill level is nearly irrelevant for me in this argument, except maybe at the NBA level.

Personally, I believe that anyone who has the coordination and skill to stop quickly and make a 15-foot shot has the coordination and skill to shoot successfully from 19’9. Once the college three-point line moves back to 22′, then there will be some separation between midrange only shooters and three-point shooters, but distance is a minimal factor to me.

I believe that the bigger factors in shooting are defense and decisions. A midrange shot moves a player closer to a defender. This requires a player to shoot quicker and possibly higher to avoid the defense. Secondly, the midrange shot, especially off the dribble, adds complexity to the decision, which impacts shooting percentages.

For my shooters at the three-point line, shooting is an if/then decision: “If I am open, then I shoot.” Nothing else matters; not distance, not a teammate being open, not the time on the shot clock, not the score, etc. (until the last two minutes, maybe). This reduces the decision-making.

When a player attacks, as in the drop coverage that Taylor described, there are more decisions. First, am I open? Second, is the roller open? Third, do I have a kick out to a shooter? Fourth, when do I stop and shoot? Can I ge to the rim? Fifth, do I shoot a jump shot or a floater? These decisions, and possibilities, absolutely affect shooting percentages. This is a major reason that players shoot 80& on this pull-up jump shot in drills as the designated shooter, but shoot 40% during games.

Therefore, the closer shot is more difficult and more complex. The three-point shot is further from the basket, which lowers percentages slightly for every foot further back, but players are compensated for this added difficulty with an extra point. There is no similar compensation for the added difficulty and complexity of the closer shot.

From the time that I coached u9s in 2001, this has been my thinking: If we have to shoot a jump shot instead of a layup, I want the shooter to catch facing the basket, and I want to shoot three-pointers because I feel that the added difficulty of the distance is easier to overcome than the difficulty and complexity of a midrange shot AND the added difficulty is rewarded with an extra point. With u9s, I believed that any jump shot was a low percentage shot regardless of distance; therefore, why not get an extra point for makes? If we shot 25% on 3s, and 30% on two-point jump shots, that is a big win for three-point shots despite poor shooting either way. That’s just math.

As an example, our offense last year scored .84 points per possession, which ranked as “excellent”. Our half-court offense scored .795 points per possession. We scored 1.018 PPP on three-point shots, and .707 PPP on midrange shots, and we had one of the best, smoothest midrange shooters in the country. Our defense gave up .698 PPP and .668 in half-court. Opponents scored .542 PPP on midrange shots, and .87 on three-point shots.

The debate, then, changes from “Are midrange bad shots?” (yes) to “Are midrange shots bad because of bad shooters or because players do not practice?” (?). I would argue that they are bad shots because the are more difficult and more complex than three-point shots because of proximity to defense and more possibilities.

As defenses work harder to take away the three-point shot, the midrange may increase in value because midrange shots move further from the defense. This, in a sense, is one of Taylor’s arguments (as well as arguing that Derozan’s midrange game has gravity that opens up better three-point shots for teammates). At lower levels, I do not believe that we have reached this point, except against a few specific defenses.

I do not outlaw the midrange shot, and we practice midrange shots (primarily because of practice variability and confidence from watching ball go through the basket). However, we hunt catch-and-shoot three point shots because they are better, easier shots that are worth more points. It is common sense to me, which is the reason that I do not understand the angst that many have, as they remote over the long lost midrange shot that is a low efficiency, more difficult, more complex shot. Is it useful on occasions? Yes. Can a great shooter succeed with his midrange game? If he is KD’s and Kawhi’s level, sure. But, as paradoxical as it seems to many, I believe that it is easier for a player to shoot 40% on catch-and-shoot three-pointers than 60% on midrange shots, and maybe we’re taking the easy out, but that seems like smart basketball to me.