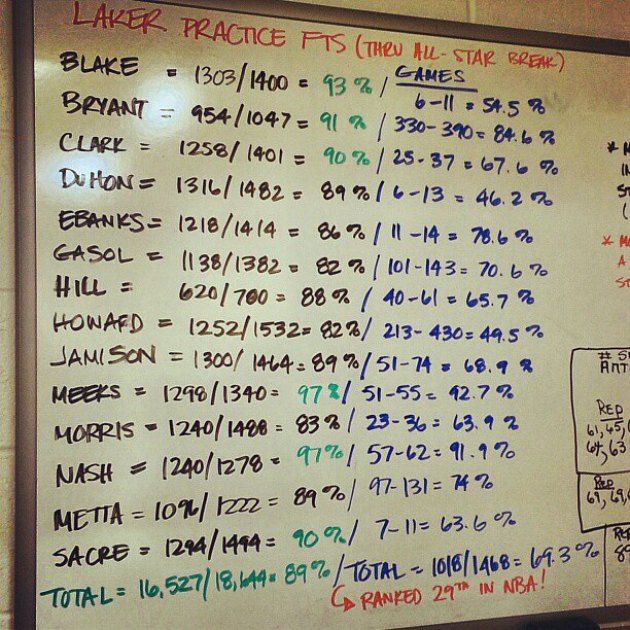

I found the picture above on Twitter last night. In a quick glance, three things are apparent:

- The idea that NBA players do not practice free-throw shooting enough is a myth.

- The idea that NBA players are poor free-throw shooters is a myth.

- The ability to make practice free throws is not correlated with successful free throw shooting during games.

Look at Dwight Howard. At this point, he was shooting 49.5% from the free-throw line during games. When he has a poor performance from the free-throw line during a game, analysts and fans suggest that he needs to practice more. He attempted 1532 shots in practice and made them at 82%. How much more practice does he need?

I have no idea how the Lakers practiced free throws or how they reached these numbers. In the limited number of NBA practices that I have witnessed, most free-throw practice occurs with nobody on the free-throw line besides the shooter and a coach underneath the basket to rebound. The player shoots shot after shot without moving from the line until he has made a certain number or made a certain number in a row.

This is block practice. Block practice leads to immediate practice improvements. In this case, Howard is the worst practice shooter at 82%. Is continuing to take more shots and making 90% of the shots leading to improvement or learning?

Random practice is used frequently by coaches instead of block practice to mimic game situations. Random practice generally involves the use of multiple skills, such as practicing dribbling and shooting together. Random practice of free throws would require a similar practice environment as that of a game, typically shooting free throws within a scrimmage.

Variable practice is used less frequently by coaches, especially with regards to free throws. When used, it is often at the end of another drill. For instance, shoot a set of 10 jump shots and finish with two free throws. In terms of overall shooting, this would be variable practice because the player shoots different shots.

However, another form of variable practice is to shoot free throws of varying distances. This is not used widely, as the free throw distance never changes, and the belief is that more practice at that singular distance will lead to more success. One common drill is to make (or swish) three shots (or five) shots in a row and take a step back. This is a form of free-throw shooting practice even though few use the drill for this reason.

Assuming that the majority of the Lakers’ free-throw shooting was in block practice conditions, this picture demonstrates the lack of transfer of block practice. Transfer is concerned with maintaining one’s skill performance from one situation (practice) to another (game). Whereas the practice performance demonstrates a certain amount of shooting proficiency, there is a lack of transfer of this proficiency from practice to games for most of the players.

Coaches often discuss different ways to make free-throw shooting more game-like, as it is hard to simulate the pressure of the game, the fatigue, the crowd, etc. This is true. There are psychological elements as well. However, the practice conditions affect transfer from practice to games.

Rather than additional repetitions, these players probably need fewer repetitions. One approach would be similar to the one that Chip Engelland used with Steve Kerr with the San Antonio Spurs:

When Steve Kerr was having a hard time shooting well coming off the bench, shooting coach Chip Engelland did something amazing. He’d sit on the bench in the empty gym and chat with Kerr, about this, that, or whatever. Then every few minutes he’d yell that it was time to shoot, and Kerr would run out on the court and take just a few shots. It got him used to sitting, sitting, sitting and then having a couple of opportunities. And it worked. (From The Art of a Beautiful Game by Chris Ballard, via True Hoop)

Engelland did not have Kerr shoot more shots. He shot less. However, he created a game-like situation: a long period of time between shots.

Why does Steve Nash’s free-throw practice transfer from practice to games as well as or better than any of his teammates? There are likely several reasons, of which one is his routine. In short, Nash uses his routine to access his long-term memory for his motor pattern. When he receives the ball, his motor pattern is in his short-term or working memory. His routine has the same effect as block practice. When players shoot the same shot over and over in practice, their motor pattern remains in their working memory and each shot is more and more consistent. However, in a game, players have to retrieve their motor pattern from their long-term memory. Nash facilitates this retrieval with his routine that closely mimics his physical shooting. It’s as if he takes a warm-up shot before his first free throw.

Whether shooting free throws from different distances or in the middle of scrimmages or with other players yelling to mimic the crowds, players need to change from block practice to more random, variable practice to improve their game free-throw shooting performance, as the Lakers’ percentages in the photo above illustrated.